My Irish Village (Creeslough)

By:

Ireland Of The Welcomes Vol. 16 No. 3 Sep-Oct 1967

My first encounter with a ghost occurred in Ireland, in the tiny village of Creeslough set down in the north-western corner of Donegal. Like the boy in the fairytale, I arrived in Creeslough by the simple procedure of following my nose. The village sits snugly at the foot of Muckish Mountain and does not differ greatly from other Irish villages of its size. It has a single street flanked by houses painted in colours which one associates with Mediterranean lands – yellow, light blue, pink and white facades fitted with doors and window frames in red, black, blue, green and brown.

The Post Office is part of the shop which sells tobacco and cigarettes, not to mention meat and cheese displayed on its counter in company with view-cards, wool, maps, toys and hosiery. A new acquisition o f the village is the co-operative self-service store, ‘Doe Co-op’, which has the rich selection of goods a rural shop requires, including even ploughs.

f the village is the co-operative self-service store, ‘Doe Co-op’, which has the rich selection of goods a rural shop requires, including even ploughs.

Creeslough’s main street is narrow and steep, and the low wall which flanks a section of it is a favourite observation post for the old men of the village. Here, close to the entrance to a pub, they can sit in the sunshine while they smoke their pipes.

The womenfolk of the village get all the news from the girl who operates the cash register in the self-service co-operative. She knows all that is worth knowing, weddings, births, deaths, the lucky winners of raffles.

I went to live at Massinass House, which once upon a time was the village doctor’s home, a stately home which offered fine ale to its guests and had many horses in its stables. Indeed it was then known far and wide for its modernity – the bathroom was done in green porcelain.

Now, however, it is an old, tired house which half-kneels by the roadside, its windows half-open as it looks sleepily out across the bay, but still retaining in some indefinable way its past aura of splendour.

The village doctor’s daughter is married and now lives in England during the winter months. Every summer she comes back to the village and the old house comes alive to the sounds of playing children and the creaking footsteps of guests who occupy the magnificent bedroom on the second floor.

‘One day soon we’re coming back for good’, says Rosemary. ‘and then the house will start to live again, with children racing through the rooms, donkeys in the stables at the back, hens picking their living outside and a cat that will sleep in the shade of the rhododendrons in the garden’.

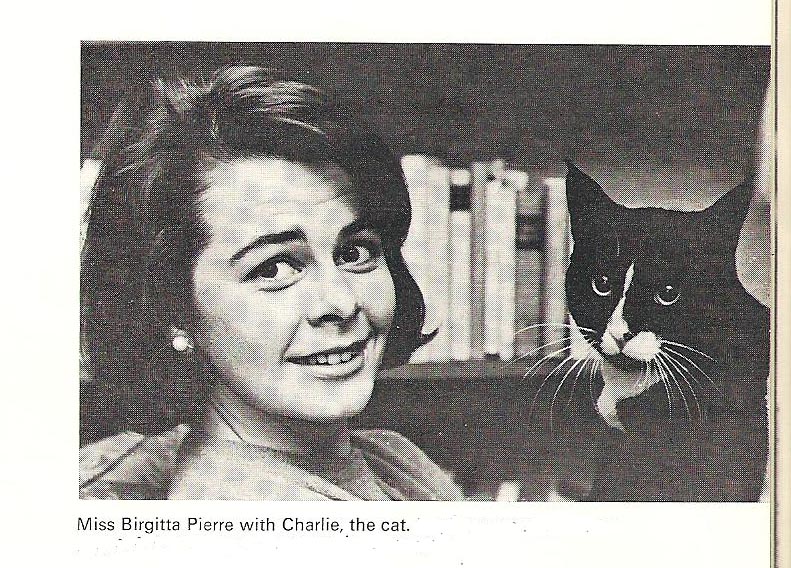

The Irish are a talkative people, of that there can be no doubt. So that a shy, nervous young Swedish guest was never given time in which to feel unnoticed, forgotten, lonely or neglected. Instead she was drawn straight away into the pattern of village life. And thank heaven for that!

Rosemary, my hostess, was no exception when it came to making a visitor feel the very centre of attraction. Of a morning, over the bacon and eggs, the tea and the toast, we could discuss everything under the sun, from religion to emigration.

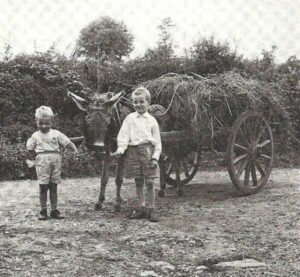

When I had been but a short time at Massinass House I happened to mention that it would be really wonderful if one could rent a little cottage and live in it for a few weeks or so. Five minutes later we were on our way to see ‘people I know’ in the village. And by afternoon on the same day I was the ‘tenant’ of a little house which stood not more than a hundred yards from one of the sights of Creeslough, the ruins of a fifteenth-century castle. My new landlord, who was busily saving his hay during the entire negotiations, rested on his hay rake and muttered something about the ghost.

‘And you wouldn’t be afeared of the ghost now, would you?’ he said to me while he wiped the back of his neck with his crumpled-up cap.

‘Of course not’, I replied, hastily. Then, thinking better of it (one can never be quite sure about such things), I went on: ‘Are there really such things as ghosts?’

He looked away towards the sun and then back to where I stood in his field. Casually he told me that ghosts abounded in the old ruined castle. . . .

‘Ghosts? Rubbish!’ I declared to the bright world bathed in the afternoon sunlight.

It was 10.30 at night when I jumped to the gentle knocking at the front door. Earlier that evening I had told myself that, should a knocking come on my door, I would first of all enquire if the ghostly arrival was of a friendly disposition. One can never be too sure.

Nervously, I moved towards the door and my first meeting with my first ghost. I opened the door. Outside stood not one but four of them. One of them had a sack of turf, another had a basket of eggs, the third had a bottle of milk, while the fourth and smallest of the quartet, aged about 4 years, carried a ginger and white kitten which possessed one black eye. One of the children said so softly that I could scarcely hear the words over the pounding of my heart:

‘Mammy and Daddy said you would need this, so we brought them along’ Then, as suddenly as they had come, they melted away into the night. And on my doorstep was the ginger and white kitten which crawled over the turf, the egg basket and the milk.

“No ghosts, to my disappointment, but the neighbour’s children who had been sent to see that ‘the young woman who lived in the empty house beside the castle ruins had everything she needed’.

I stood for a minute or two on the doorstep with the mewing kitten in my arms. Outside somewhere a cricket chirped. I felt strangely welcome.

Before I left home on my trip to Ireland my friends and acquaintances had indoctrinated me on the ‘friendliness of the Irish’, their hospitality, their warmth, humour, and their captivating philosophy of life. I got so much of this that for a time I doubted its veracity. Now, however, it was being spelled out for me.

I continued to sit up, waiting for the ‘real ghosts’ to show up. It was 3 o’clock when I dropped off to sleep, to be awakened by more knocking on the door.

This time Rosemary stood on the threshold. Did I find it lonely here in the empty house with only the kitten and the mice for company? Had I sheets? An electric ring on which to prepare food and boil water for the tea? Plates and cups? Cutlery? No? Then come with me back to Massinass and we will get all you need.

Within the hour I was back with everything necessary for continued survival. An escort of children accompanied me, each carrying something for my new home.

And they helped me to wash and scrub, to clean the windows; and they played with the kitten and gathered small pieces of kindling for the turf fire. Susan Kelly, my neighbour’s eldest daughter, showed me how to light a turf fire, for those unversed in this ritual can spend hours in fruitless efforts to get a fire going.

‘Put the small twigs down at the bottom, then small bits of turf on top of them, like this’, she paused to break a sod of turf across her knees, pulling small pieces from it which she then laid in a semi-circle in the grate. ‘Now you take a few bigger pieces of turf and put them on top of the smaller pieces; and then some more turf. And if you want it to light very quickly then you pour on a little paraffin’.

To me it was a strange custom, this using of turf as a fuel. In a few minutes the flames grew stronger, the little pieces of turf soaked them up, hungrily, and soon the mass of turf glowed red in the grate sending an even, strong warmth out into the room, while a spiral of blue smoke crept up the chimney. Later in the evening I spread ash over the still glowing turf, following Susan’s instructions, to ensure that the fire would ‘keep in’ until the following morning. And it did. Next morning all that was necessary was to lay fresh turf on the half-smothered but still ‘live’ ashes, and hey presto! my fire leaped again to life.

Travelling through the Irish countryside during the twilight hours one can see the thin wisps of blue peat smoke rising from almost every chimney and smell that strange clean odour of burning turf.

Within a few days of my arrival I was known everywhere in the village as ‘the Swedish lady down at the castle’. And this, too, despite the fact that I seldom showed myself in public in the beginning, being content to sit on my doorstep in the sunshine, the kitten in my lap, a mug of coffee in one hand and an open book in the other. I was fascinated by the almost sub-tropical vegetation, the powerful contours of the countryside and the constantly changing light over mountain and sea.

Every evening I went to Kellys, my nearest neighbours, to fetch the milk. The big kitchen with its huge open hearth and its stone floor seemed always full of children, dogs and cats. Yet when I counted the children later I was surprised to find they numbered only four, Susan Frank, Agnes and Hugh.

In the beginning the children were inclined to be shy with this strange ‘foreigner’ and they sat on the sofa, quietly, like young birds on a perch, each time I entered the kitchen. But in no time at all their shyness vanished and they began to tell me about school and about their friends. Four-year-old Hugh went so far as to climb up on my lap.

When the milk can had been filled and I rose to go, Mrs. Kelly would appear startled, and say: ‘What hurry is on you? You know well that when God made time He made plenty of it’. What can one say when faced with such an argument?

Tea in the evenings with the Kelly family became a regular ritual. Slowly I was learning to adjust my ears to the Donegal dialect, in which Creeslough is pronounced ‘Creechluh’, Muckish becomes ‘Mookish’ and Mr. Moore sounds like ‘Mester Mure’.

Josie Kelly told me, and with no small degree of pride, too, that the previous year he had exported eight tons of potatoes; and he was fascinated by the thought that somewhere in France or in Spain people were sitting down to eat them. Just how many tons he would export in the current year was a matter for speculation . . . but if the good weather continued to hold. . . .

Ten days of clear, bright sunny weather changed suddenly one night. The morning broke with a storm and a cold blustery wind blowing the rain helter-skelter. Josie claimed that this storm was the worst to rage across Donegal in human memory at that time of year.

Every now and then I looked in on Massinass House, and on one such visit I met Mrs. Sheila Kelly, an 80 years old lady who lived in a tiny cottage almost drowned in ivy and wild fuchsia on the outskirts of the village. Every morning of her life she went to Massinass House in order to drink a cup of tea and read the day’s newspapers. When she learned that I lived almost in the ruins of the old castle she was greatly interested, and she thereupon recited for me a number of ballads devoted to the bloody history of this castle. In her soft, singing Donegal accent she recited three long ones without an instant’s pause or stumble.

The ballads dealt with not alone the fierce battles of the past but also with a tragic love story, that of the beautiful Eileen and the brave young Turlough O’Boyle.

. . .

And in Doe Castle graveyard green beneath the mouldering soil

Maolmurra’s daughter sleeps in death with Turlogh og O’Boyle.

And fishers say until this day a boat is seen to glide

At dead of night by pale moonlight there on the silvery tide,

And in the boat two figures sit and on each face a smile,

They say it is the lovers, Young Eileen and O’Boyle.

Close by the walls of the castle ruins there is a tiny burial ground containing a headstone under which the lovers are said to rest forever. The stone lies against the north wall and is half-hidden by two high-growing rose bushes heavy with blooms. …

When I had heard these tales of bloody battles and of unhappy love affairs which had been woven into the history of this old castle, I felt surprised that the ruins went unhaunted. Or … was this really the case? Perhaps my Irish friends are right when they say that only certain people possess the ability to see the Little Folk, the Leprechaun and ghosts?