Shooting Guns, Robbing Trains and Jail Time in Kilmainham

By Marie Duffy

Throughout the War of Independence, Britain failed to recognize that the IRA was a national army fighting for Ireland’s freedom, Britain claimed they were dealing with a civil disorder rather than a war. They refused to send over the British army. By 1920 Lloyd George had recruited soldiers that had fought in WW1 and when the first of them arrived in Ireland they became known as the ‘black and tans’ because of their uniforms.

The ‘Black and Tans’ were unable to deal with the guerilla warfare of the IRA and became very frustrated, there was no front line, – or rather the front line was everywhere ‘the enemy was invisible, yet he was everywhere’. This led them to commit dreadful crimes. They were given authority to arrest and imprison without trial anybody suspected of membership of the IRA. Their horrific policies led them to be hated by the people. The destruction of properties such as creameries invaluable for community prosperity was common. Local people became involved in the fight for Irish freedom in retaliation for their brutality.

A truce in July 1921 between the Irish and the British crown forces led to negotiations for a treaty. On December 6 1922 the Anglo Irish treaty was signed. This stated that the 26 southern counties would become the Irish Free State while the remaining six counties would still be under British rule and occupied by British troops. The treaty brought about a bitter split in the IRA, it was now divided into two hostile groups- those anti–Treaty and those pro-Treaty. These two groups became known as the irregulars and the regulars respectively.

The Dail approved the treaty in Jan 1922 with 64 in favour with 57 against. This was followed by a bitter debate in which those backing the treaty were accused of treachery. DeValera and his supporters withdrew from the Dail in protest.

Following the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson, the military advisor to Northern Ireland, the Irish government was pressured by the British government to crack down on the irregulars. In June 1922 civil war blazed and tragedy hit Ireland. Irish men and women were now fighting Irish men and women.

The irregulars increasingly resulted in guerilla warfare, however, it was not as successful as it had once been in the War of Independence. This time both parties had knowledge of the countryside and though safe houses were provided to some extent to the irregulars, the majority of public opinion was very much in favour of the government. The Catholic Church backed the government, and this helped sway public opinion. The emergency power acts adopted by the new government allowed for the arrest and detention of anyone suspected of being a danger to public safety.

The McGee family in Feymore, Creeslough, were very much involved in fighting for Irish freedom, like many others in the area. They helped in every way possible to help Ireland gain independence from Britain. During the War of Independence they actively helped in the battle against the Black and Tans.

Sisters Katie, Sadie, and Mary were all active members of Cumann na mBán. They helped look after wounded soldiers, fed them, and clothed them. Members were well versed on first aid and nursing. They were expected to be able to use, care, clean and load rifles. Physical drills were also practiced. Cumann na mBán members were also extremely patriotic and had high regard for the Irish language.

The Mc Gee house in Feymore was widely regarded as a safe house for any Irish man on the run from the British forces. This meant that it was often subject to raids by the Black and Tans. Patrick McGee their brother was a member of the First Northern Division of the IRA. He was disgusted by the treatment of the ‘Black and Tans’ on the Irish people, and he was often a part of attacks against their members.

Following the negotiations of 1922, the family was outraged and disgusted when the treaty was signed and Ireland was divided. They felt betrayed and quickly opposed it. Society now became split up and comrades who fought shoulder to shoulder through years of struggle against a common enemy were now pitched in battle against each other, in a war that divided families and friends in succeeding generations. However, the McGee’s continued to fight for their cause – a united Irish Republic.

The Irregulars caused chaos for the government. Attacks on free-state garrisons, assassinations, and damage of public property were all widespread. Communication such as mail was interfered with. Railways, roads and bridges were all damaged to cause havoc, chaos and confusion for the government.

In early 1922, two armed women held up a train that was traveling through Creeslough. They searched the train and removed parcels containing the Derry Standard and Belfast newspapers. The parcels were then set alight and destroyed. This was due to the Sinn Féin ban on Northern Ireland manufactured goods.

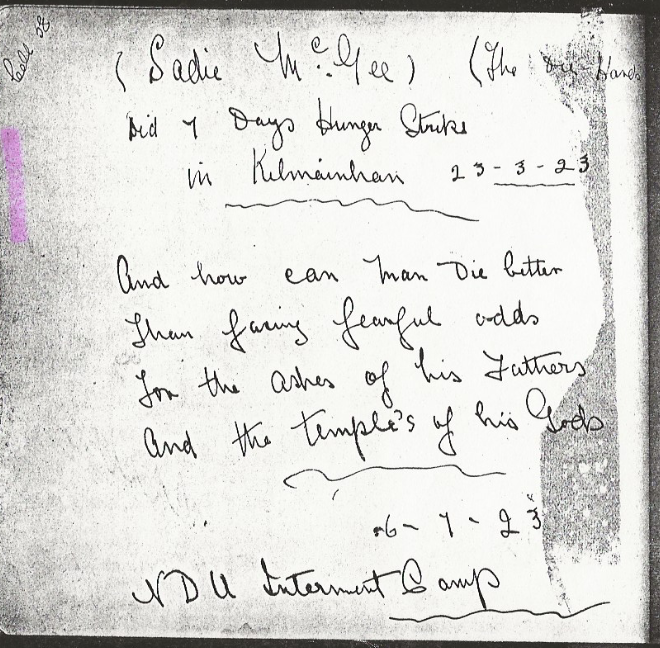

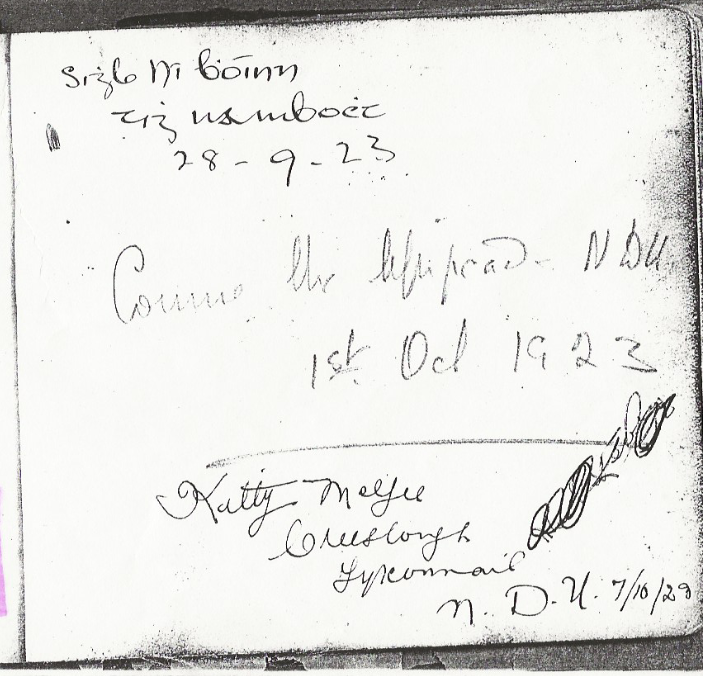

On Monday morning the train and the Belfast papers were again targeted and burned by armed women once again. These armed women were in fact members of the McGee family. Shortly afterwards Katie, Sadie, and Mary were arrested and sent to Kilmainham jail. While there, Sadie went on 7 days hunger strike and she was later transferred to the North Dublin Union (NDU) Internment camp. She was a lady who continued to show great patriotism and strength, which she illustrated in various prison autograph books.

‘Cowards cast me to prison but you’ll never bend our will, we never called you masters and by heaven we never will’ Katie was also later transferred to NDU on 28 September 1923. Mary was released on 16 September 1923.

Patrick was also imprisoned. While there, like many other prisoners, he went on hunger strike, in protest against his imprisonment. He later attempted to escape from prison along with other prisoners by digging an underground passage that led to a drain, which reached the Liffey close to the camp.

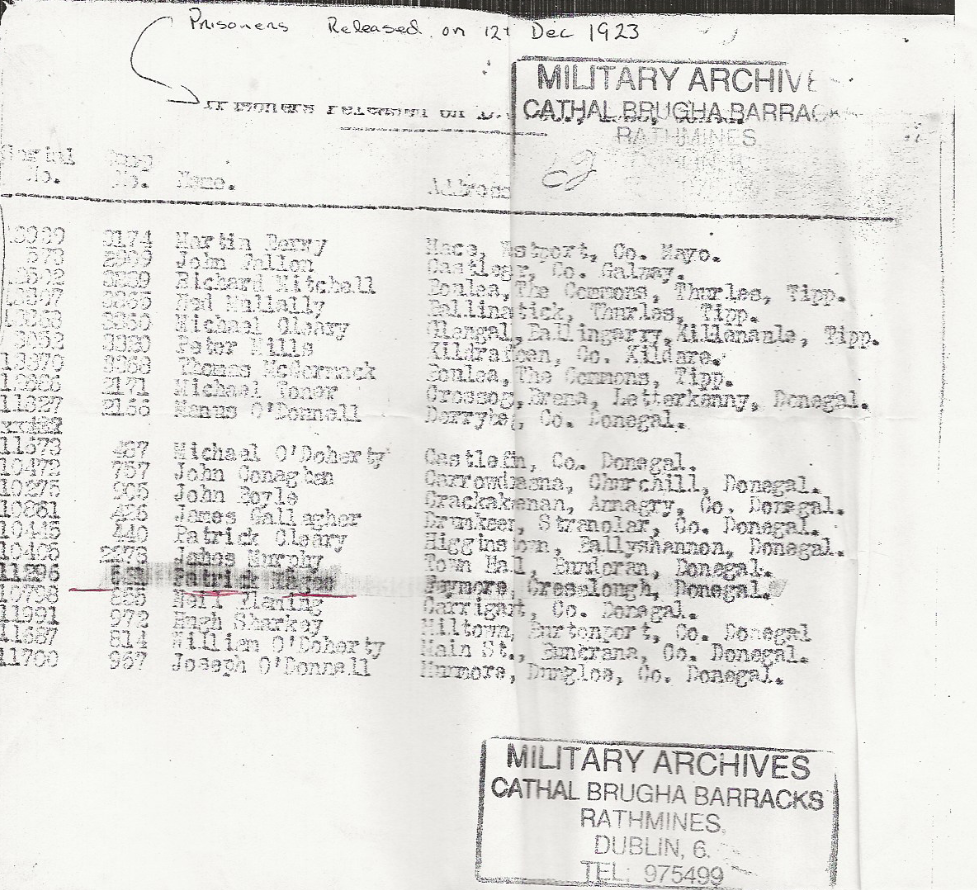

On 14 October 1922, approximately 160 prisoners escaped from Droichead-nua internment camp. However, there was great danger and Pat almost drowned, fearing for his life he returned back to the prison where he was placed immediately into solitary confinement and given just water. By the end of 1924, all the internees were released following a truce between the two sides. However, the war caused a deep-rooted division in Irish society, injecting bitterness and ill-feeling into all aspects of life.

Following their release, Patrick, Sadie, Mary and Kitty felt rejected by the country in which they were now living in. They felt bitter and disgusted following the treaty. They were also subjected to scorn and ridicule from the surrounding people who were pro-treaty. The catholic priests refused to listen to confessions or give communion to people who supported the republican ideas. Free State forces used various tactics to try to break the spirit of these women and when all else failed they resorted to defamation of character, with officers broadcasting the vilest and most degrading allegations about the women – all this for simply upholding the principles of the Republic.

Having struggled to make the dream of a united Ireland a reality, many republicans felt betrayed and disheartened by the signing of the treaty, they felt that the treaty was a direct insult to all that had died in Ireland’s struggle for freedom. Feeling dejected Sadie, Mary, Pat and the rest of their family later emigrated to America.

Mary later married a German, Oscar Schaffmit. Katie married a railway worker Barney McDonald. Pat married Mae-Ann Conway from Co. Derry and became a stonemason. Although they had left Ireland behind them, they never forgot about Creeslough and they still longed to be at home in Feymore. They kept a keen interest in Ireland and what was going on there despite never returning to their real home in Feymore. In recent years the daughter, granddaughter and great-grandchildren of Patrick McGee returned to Creeslough to see where their family had originated from. They were humbled to see the old homestead where her family had started out. Kaye spoke of her father’s love for Ireland and how much he missed his homeland and how he ‘never really settled’. The Mc Gees were just another Irish family who were forced to emigrate for a better life.