The Dunfanaghy Workhouse in County Donegal stands as a poignant reminder of the grim realities of 19th-century Ireland, particularly during the Great Famine (An Gorta Mór). Built as part of the Irish Poor Law system, the workhouse was a place of last resort for the destitute and impoverished. Today, the building has been restored and serves as a museum and heritage centre, preserving the stories of those who lived, suffered, and died within its walls.

History of the Dunfanaghy Workhouse

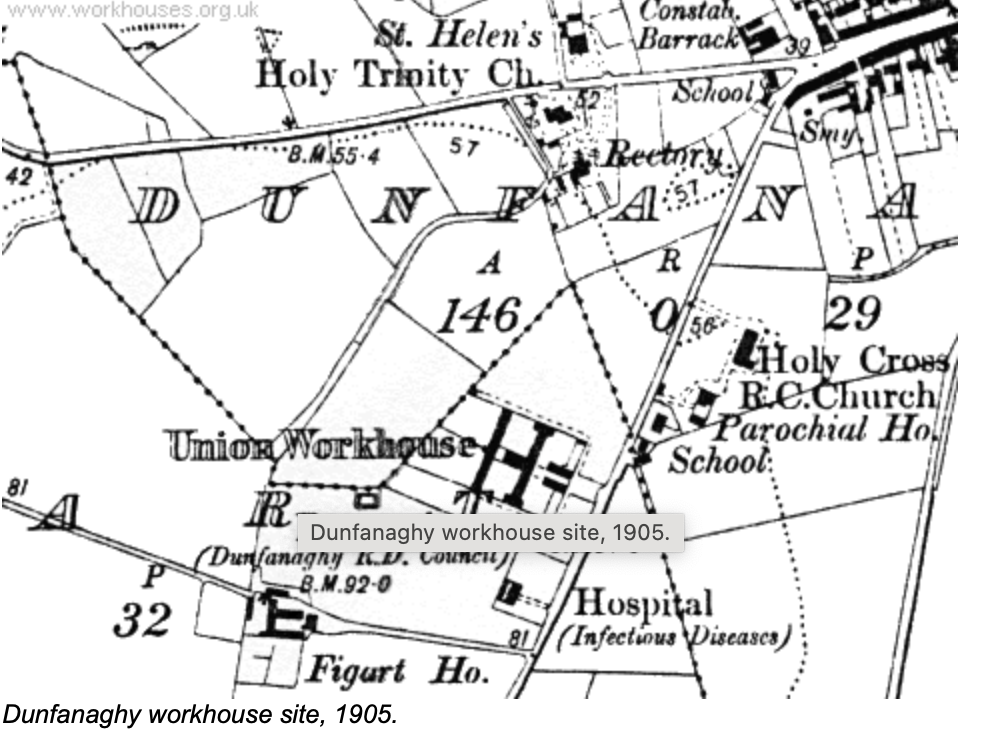

Construction of the Dunfanaghy Workhouse began in 1843, and it opened its doors in June 1845. It was the last of the originally planned workhouses in Ireland to open, built on land purchased from Alexander Stuart of Ards in 1842 at a cost of £5,000—equivalent to roughly €356,000 today. Like many of its counterparts across Ireland, the workhouse was designed by George Wilkinson, the Poor Law Commission’s Chief Architect, and built using limestone quoins and sandstone. Originally designed to accommodate 300 people, its capacity was doubled to 600 during the famine years due to the overwhelming demand for poor relief.

The Poor Law System and the Workhouses

The Poor Law Act of 1838 introduced the workhouse system into Ireland, with the country divided into Poor Law Unions, each responsible for operating a workhouse as a centre of relief. The Dunfanaghy Poor Union included townlands such as Dunfanaghy, Creeslough, Derryreel, Falcarragh, and Derryveagh, covering a population of 15,793, according to the 1831 census.

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse followed the architectural blueprint of many other workhouses designed by Wilkinson. It contained a reception area, dormitories, workshops, a kitchen, and schoolrooms, all surrounded by high stone walls. A Board of Guardians, drawn from local gentry, landowners, merchants, and justices of the peace, oversaw the administration of the workhouse. Among them were prominent local landlords like Stewart, Olphert, and Hill. The daily operation was run by the Workhouse Master, supported by staff including a matron, porter, clerk, schoolmistress, doctor, and nurse.

Opening and Purpose

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse opened on June 24, 1845, with five paupers admitted on the first day. However, with the onset of the Great Famine, numbers surged. By 1847, known as “Black ’47,” the workhouse was overwhelmed with the number of destitute people seeking shelter. Conditions deteriorated, and by 1851, 481 paupers were living in the workhouse. Although the Dunfanaghy Union escaped the worst of the famine’s devastation compared to other regions, the workhouse still bore witness to immense suffering.

During the famine, inmates survived mainly on soups and stews, often supplemented by fish, seaweed, and crustaceans gathered from the nearby shoreline. Despite the relief efforts, many did not survive the crowded, unsanitary conditions, with diseases like typhus and dysentery claiming numerous lives.

Living Conditions and Expansion During the Famine

Life in the workhouse was harsh. Men, women, and children were separated into different sections, and families were often torn apart. As the famine intensified, overcrowding worsened, and the workhouse expanded to accommodate more people. Although the Dunfanaghy Board of Guardians insisted on using flagstones instead of earthen floors, conditions remained basic and squalid.

Despite these hardships, the workhouse provided the only means of survival for many, though disease was rampant. Starvation and overcrowding led to numerous deaths, with many inmates never leaving the workhouse once they entered.

The End of the Workhouse System

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse remained operational until 1917, closing shortly before the disestablishment of the workhouse system in 1922 following the creation of the Irish Free State. After its closure, the building was briefly used as a co-op and then abandoned. It fell into disrepair and was used as pasture for local farmers until it was declared a heritage site in the 1980s. In 1995, the Dunfanaghy Workhouse reopened as the Donegal Famine Heritage Centre, 150 years after its original opening.

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse Today: A Museum and Heritage Centre

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse has been carefully restored and transformed into the Workhouse Famine Heritage Centre, where visitors can learn about the workhouse system, the Great Famine, and the social and economic history of 19th-century Ireland.

The museum features:

- The Great Famine: Exhibits that explore the devastating impact of the famine on Donegal and the wider Irish population.

- Life in the Workhouse: Displays recreating the harsh conditions faced by the inmates, with detailed accounts of their daily lives.

- Local History and Social Context: The heritage centre delves into the broader history of the Dunfanaghy area and the social factors that contributed to widespread poverty.

Importance of the Dunfanaghy Workhouse

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse stands as a testament to the immense suffering endured by the Irish people during the Great Famine and the harsh realities of the 19th-century poor relief system. By preserving this site, the heritage centre ensures that the stories of those who passed through its doors are not forgotten. It serves as a vital educational resource, offering visitors a window into one of the most challenging periods in Irish history.

The Dunfanaghy Workhouse is a site of deep historical significance, providing a tangible link to Ireland’s past. Its transformation into a museum ensures that the suffering and resilience of those who lived there during the famine years will be remembered for generations to come. Visitors to the heritage centre not only gain insight into the grim conditions of the workhouse but also a greater understanding of the social and economic forces that shaped modern Ireland.